Bonnie and Clyde remain two of the most notorious outlaws in American history. During the Great Depression, they roamed the country, targeting gas stations and small businesses. With desperate times driving many to crime, the duo saw quick cash waiting beyond the law and chose to embrace the outlaw life. For more, visit dallaski.

Clyde Barrow

Clyde Barrow was born on March 24, 1909, in Ellis County, Texas, just outside Dallas. He grew up in a poor farming family but discovered a passion for music early on. He sang, played an old guitar, and even taught himself saxophone. A music career seemed possible until life intervened. As a teenager, Clyde tried to enlist in the U.S. Navy but was rejected during the medical exam because of lingering health issues from childhood malaria or yellow fever.

Under the influence of his older brother Buck and a shady family friend, Clyde drifted toward crime. His first arrest came in late 1926 for failing to return a rented car on time. Although the charges were dropped, the arrest stayed on record. Soon after, he and his brother were caught stealing a truckload of turkeys. Clyde faced additional charges for safecracking, shoplifting, and auto theft. He spent his ill-gotten gains on sharp suits, ties and—most importantly—his beloved hats, determined to escape the poverty he despised.

Bonnie Parker

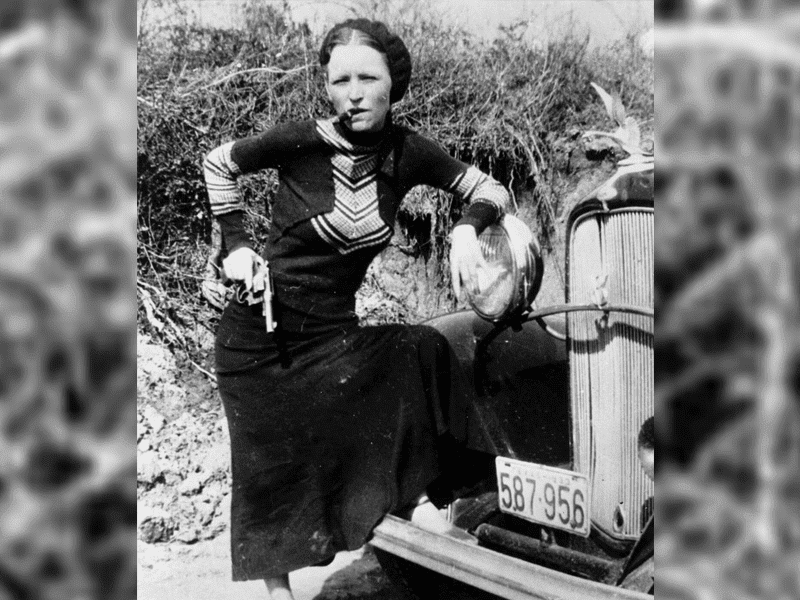

Bonnie Parker was born on October 1, 1910, in Rowena, Texas. She lost her father early, and her mother supported three children on a seamstress’s wage. The family later moved to Cement City, an industrial suburb west of Dallas. Even as a child, Bonnie was determined to improve her family’s situation. She loved chic dresses and elegant hats but was too young at ten to find steady work.

Just before her 16th birthday, Bonnie married Roy Thornton. The union was unhappy and soon fell apart, though they never legally divorced. Bonnie kept her wedding ring until her death and even had a tattoo of a heart with both their names on her inner thigh. After returning to Dallas, she worked as a waitress and, by eighteen, kept a small journal. In it, she wrote about her loneliness, her frustration with life in Dallas, and her passion for photography.

Love at First Sight

According to historical records, Bonnie and Clyde first met in January 1930 at a mutual friend’s house. There was love at first sight, and over the next few months they were inseparable.

Trouble followed quickly. In 1930, Clyde was arrested and sent to Eastham Prison. Bonnie smuggled in a gun to aid his escape, but he was recaptured. Inside, Clyde faced brutal treatment. When another inmate assaulted him, Clyde defended himself and beat the man to death—their first killing. Another prisoner took the blame and received a life sentence. Days before his scheduled parole, Clyde severed two toes to avoid forced labor in the prison fields. He was released with a permanent limp.

Upon release, the pair plunged into a relentless crime spree.

The Early Heists and Killings

By 1932, Clyde had teamed up with Ralph Fults and Bonnie to rob small shops and gas stations. Their dual goal was to raise money and plan a mass prison break from Eastham. A failed hardware store heist landed everyone but Clyde behind bars. Bonnie’s stay was brief; the grand jury declined to indict her. Once freed, she rejoined Clyde, and they resumed their raids.

On April 30, during another robbery, they shot and killed a store owner who resisted. That killing marked a chilling escalation. Soon after, Clyde and a gang member named Hamilton, drunk and reckless, murdered a sheriff and two deputies.

Their stolen car became a rolling arsenal, loaded with pistols and hunting rifles. Bonnie mastered firearms, too. She likely understood that this path led to only one end—death—but it was more thrilling than the monotonous life she’d known.

Expanding the Gang

In late 1932, the gang gained a new recruit: 16-year-old William Jones. The following year, Clyde’s brother Buck joined after his release from prison, bringing along his wife Blanche. The group holed up in Joplin, Missouri, living recklessly—gambling late, drinking heavily—and neighbors often heard gunshots and called the police.

On April 13, police surrounded their hideout. Clyde, Buck, and Jones opened fire, killing a detective and mortally wounding another officer. The gang escaped but left behind nearly all their belongings, including incriminating photographs.

Bank Robberies Were Rare

Despite their cinematic reputation, Bonnie and Clyde rarely targeted banks. Between Texas and Minnesota, they made only two serious attempts: an unsuccessful heist in Lucerne and a successful robbery in Okabena, Minnesota. Most of their jobs involved small grocery stores and gas stations. These quick strikes minimized risk but delivered meager payouts. To keep the cash flowing, they had to hit more targets—making it increasingly difficult to stay hidden. Bonnie often stood lookout, waiting in the car or at a nearby hideout.

The End of the Outlaws

On May 23, 1934, Louisiana state troopers laid a deadly ambush. They used former associate Henry Methvin as bait. When Bonnie and Clyde drove up, the officers unleashed over 130 rounds into their stolen Ford V8. The pair died side by side in the car. Officers recovered an arsenal of weapons, thousands of rounds of ammo, and fifteen sets of license plates.

News of their deaths spread like wildfire. Thrill-seeking crowds swarmed the crash site. One woman cut bloody locks of Bonnie’s hair and bits of her dress into souvenirs for sale. Others scavenged spent shell casings and torn cloth. A man even tried to saw off Clyde’s left ear.

Although they wanted to be buried together, Bonnie’s mother—never approving of her daughter’s choices—laid her to rest in a separate Dallas cemetery. Clyde was interred next to his brother under a joint headstone that reads: “Gone But Not Forgotten.”